There were times during the process when I became frustrated with the amount of time passing by. I find that many of my clients, most of whom are in their eighties or nineties, lose momentum after they’ve reviewed the first draft. It’s a conundrum for me. It’s really important to me that every client is comfortable with the process and feels that we are working together at a calm, serene, unhurried pace. At the same time, I like seeing projects get done. I like handing clients their completed books. I like receiving photos of their book signings and seeing forwarded emails from their readers saying how much they are enjoying the book.

This client was two days shy of eighty when we began her memoir; in fact, I was in town to attend her eightieth birthday party the week we sat down for our first interview. In the three years that followed we had over thirty weekly phone interviews, most of them lasting about two hours; and three long-distance visits, two by me to her home in Colorado and one by her to my home in Massachusetts.

When prospective clients ask me how long the process will take, I always tell them the answer is probably in their hands. I don’t mean to suggest that I can work at any speed necessary, but when I’m not writing memoirs I’m a journalist for a daily paper; tight deadlines and fast turnarounds are in my professional DNA.

So maybe I’m a little bit too deadline-oriented when it comes to completing memoirs. But whenever I discuss with colleagues the challenges in our work, “keeping the process moving” is always number one on my list. I’m always seeking out advice on how to keep clients from bogging down.

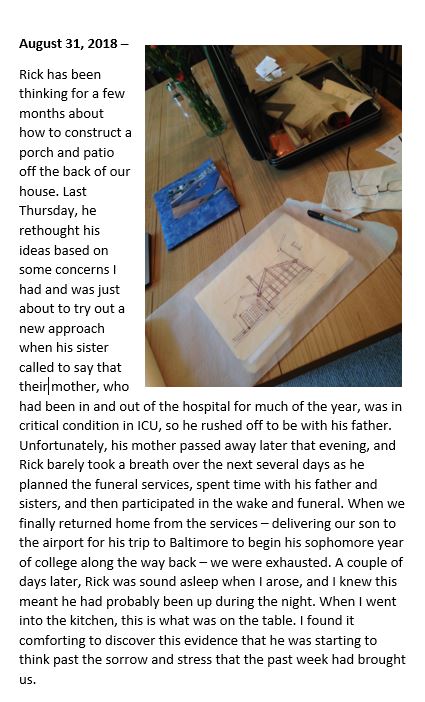

The client whose project went to print last week is now one month shy of eighty-three. Fortunately, she’s vibrant and healthy, and likely has many years left in which to enjoy sharing her story with readers. Still, projects that take a long time to complete run into the problem that lives change during that duration. In the three years we’ve worked on her book, this client had two major family celebrations that she wanted to add in after the first draft, and her husband went through a significant medical problem. True, all of those details made the book ultimately richer, but they also required us to keep rewriting our ending. And, of course, not everyone has as good luck as my client did over the course of three years; projects can fail to materialize entirely due to health problems, life changes or deaths.

So: How long should a project take and what can you do if it’s taking longer? Faced with the carrot-or-stick construct, I always opt for the carrot, gently creating aspirational pictures for my clients about their book signings or how satisfying it will be to have the completed memoir in hand. Even showing them a cover design can help move things along: once the project looks more like a book and less like a manuscript, progress sometimes quickens.

Other times I try to get inside my client’s head and see it not from my perspective – let’s get this book done so everyone can enjoy it! – but instead consider whether there’s something they are seeing that I am not. For example, when another client I’m currently working with inexplicably bogged down, I remembered that he had given me a long essay he wanted to have included in the book. I had pulled some useful details out of his essay but left the rest of it out because it related to only a very short time period in his life and didn’t really mesh with the narrative style I was using to tell his story, but it occurred to me maybe he was having trouble letting go of the text he’d already written back when he was trying to write his memoir himself. Maybe he had always imagined that essay appearing in print but was self-conscious about saying so since I had obviously made an editorial judgment when I left it out. So I went back to my first draft and worked it in, and now he’s ready to sign off on the project.

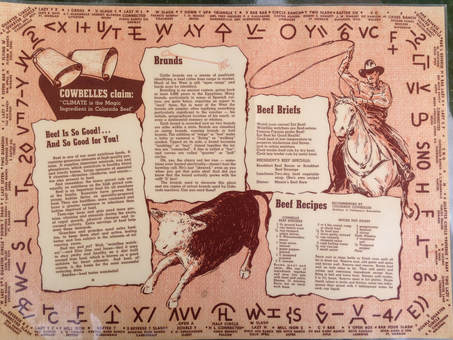

And then there are photos. Selecting pictures is probably the biggest factor in what causes my clients to bog down. Faced with 150 pages of text and 500 photos they’ve collected in a shoebox, they can never decide what can go in and what should keep out. So, with guidance from some of my colleagues in the personal history field, I’ve created a cover sheet, a checklist of sorts, to help them winnow down their expansive, often disorganized photo collection into the few snapshots that best reflect their story – mostly by choosing only those photos that specifically reflect something included in the narrative.

Ultimately, of course, there’s something to be said for patience, and assuming the project will take the time it needs. Maybe my journalist tendencies prompt me to chomp at the bit, but my memoirist side reminds me that some stories need to be told slowly, with plenty of time for reflection and rumination. And for photo collecting. And in the end, the waiting is always worth it.

Do you feel stuck on any stage of your memoir? Contact me any time to discuss how I can help!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed