My parents would both be great subjects for memoirs. But in response, I say: “Surgeons don’t operate on their own family members.” When working with memoir clients, the more objective I can be, the better. I want to hear their stories through their eyes – without any bias of my own.

Nonetheless, that didn’t stop me from agreeing to take on a memoir project with my mother’s elder sister. Though she and I had always been close, it’s the affection of an aunt and a niece a generation apart, living two thousand miles from one another: an acquaintanceship, though fond and familiar, still limited to one or two visits a year, occasional newsy emails and phone calls when the mood struck one of us.

But as I heard her stories, my usual professional dispassion began started to corrode. We were related by blood and DNA and history, and her stories were also my stories – stories I hadn’t necessarily heard before. As she told me about her forebears, I saw my own backstory filling in with details I’d never known.

The Eastern European immigrants who took their tinker trade from the alleyways of Poland to the plains of Nebraska. The Chicago aristocrat who lived in a hotel in order to avoid ever having to learn to cook. The midwestern business executive who gave up his downtown job to become a Colorado rancher, and his wife, who left her North Shore country club circles to help transform an old silver mining town into a hub of culture and intellect.

These were my ancestors and my relatives, as well as my aunt’s.

Naturally, my mother had access to all this same family lore, and she’d passed some of it on to me over the years, but like most children, sometimes I listened and sometimes I didn’t; sometimes she told stories in logical sequence and other times she recounted bits and pieces. This is exactly what I tell my clients about why they need to commit their anecdotes to the written word – because even if you think you’ve passed it all along to the next generation, they might not have been listening all that well. It turned out I myself hadn’t been listening all that well – until I approached the same stories in my professional role.

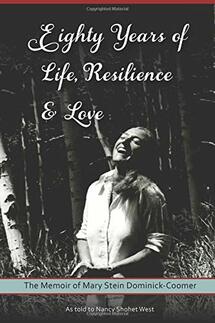

I appreciated and loved my aunt – but I knew her the same way my own young nieces now know me: someone who has been a grownup for my entire lifetime. Not until writing the memoir did I understand her life in its full-color, three-dimensional reality. She wasn’t just my aunt, or my mother’s older sister, or my cousins’ mother. She was a young girl who learned about horses and environmental stewardship from her father. She was a teenager whose mother sent her away to boarding school when she would have much rather stayed with her family. She was a young woman whose zest for romance ran up against the era’s lack of legal birth control. She was a middle-aged mother who struggled for years to recognize her spouse’s alcoholism. She was a senior finally set free by divorce, a move back to the hometown she loved, and a septuagenarian romance she believed had been her destiny all along, leading to a third marriage shortly before her eightieth birthday.

I still maintain I could never objectively write my parents’ memoirs. And perhaps the project with my aunt was not the best example of my usual approach to work either. But I’m glad I did it. It taught me about my aunt. And it taught me about myself, in a way that I never imagined a professional undertaking could.

Curious about how to approach your own memoir -- or that of someone else in your family? Contact me any time to discuss!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed