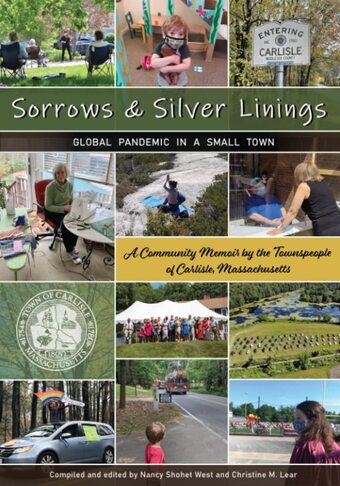

Yesterday I celebrated the launch of a different kind of project: a community memoir, exploring the ways that individuals in my hometown of Carlisle, Massachusetts experienced the first eighteen months of the COVID pandemic.

Entitled “Sorrows & Silver Linings: Global Pandemic in a Small Town,” the project began last August, when my friend Christine reached out to me with her idea that there needed to be a way to preserve as a historical record the experiences that townspeople have had during the peak of the COVID pandemic. I’m a journalist and memoir writer; I know how to interview people and capture their stories. Christine, by contrast, is a master of community organizing and project management. She knows how to draw people into an effort and make it all run smoothly. We realized that by combining our skills, this was something we could do.

We put out the word through numerous communications channels asking people to share their stories about the pandemic. These channels included local Facebook groups; our own personal Facebook pages; a townwide listserv; our town’s Recreation Commission, Council on Aging, library, three churches, and public schools; and word of mouth. To our surprise and delight, we quickly had 84 responses, from people ranging in age from 8 to 82. We had young parents and senior citizens; elementary, middle and high school students; Select Board members and teachers; EMTs and nurses and doctors; Boy Scouts and ministers; artists and athletes. Over the course of eight weeks in September and October, each participant met with me for an interview lasting about twenty minutes. Nearly all of them were in person; a few were virtual. The stories they shared were a remarkable reflection of what life has been like during this pandemic.

Some people created things. Barbara sewed masks. Jacob, who is 13, learned to make dinner. Theresa painted rocks and left them on local trails for walkers to find.

Some people suffered losses. Karen lost her father. Nazma lost her mother. Gwen lost an older sister. Caroline lost her children’s father.

And some people got COVID: Lillian, Cory, Teydin’s children, Jimmy’s dad.

Good things happened too. Cameron went running every day. Melinda’s daughter got married. Will moved to a beach house in South Carolina with nine new friends. Susie and Nick had a baby. Lots of dogs and cats moved to town.

People made great achievements. Deborah became a firefighter. Deedy graduated from college and started her dream job in New York City. Stephanie worked hard and trained hard, and now has both a triathlon medal and a big professional advancement to show for it.

Happy and sad, upbeat and poignant, optimistic and anxious, all of these stories paint a picture of what life was like in Carlisle when COVID struck in spring of 2020.

Last week, my collaborator and I attended a School Committee meeting so that we could present a copy of our book to the school library. The School Committee chair said something interesting. “I’m so happy it’s a book,” he said when we handed our book to him. “Not a website; not a blog; not a video series. A real book.” That meant a lot to me, as a writer. It was an important and appreciated reminder that books are still often our most precious historical records.

When we held our launch, to which the whole town was invited, we made nametags for every participant in our project. Above each name was printed the word “storyteller.” During the four months we worked on this project, I usually used the word “participant” when I referred to the many people of all ages who had signed up for interviews. But when it came time for all of us to gather together for the book launch, I thought anew about the 84 individuals who had mustered the courage and humility to share their stories and realized that’s what they were: storytellers, observing that most primal human instinct to share what had happened to them.

My collaborator and I feel humbled and honored that so many people were willing to let us narrate their experiences. It was a joy for us to unveil our book and share it with our small community – and with the world beyond.

Want to know more? Click here for a peek at "Sorrows and Silver Linings: Global Pandemic in a Small Town."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed