My grandparents’ life had long been a source of interest to me, both as a child and as an adult. I had tried to absorb what I could, based mostly on what I witnessed or heard during our twice-yearly trips from Massachusetts to Colorado or the details my mother told me, but not until my aunt, their eldest daughter, hired me to do a memoir project with her did I come to a more meaningful understanding of who they were.

I knew my Chicago-born grandparents and their three daughters had started vacationing in Colorado shortly after the end of World War II and made the decision a few years later to move to Aspen permanently, but until I was interviewing my aunt for her memoir, I didn’t fully appreciate the vision they were pursuing: my grandfather’s dreams of being a western rancher instead of a Chicago businessman; my grandmother’s prescience that this newly developing ski resort could, with the right guidance, become a rich cultural hub of music, dance and ideas and not just an apres-ski bar scene. I knew my grandfather was appreciated and respected in his new hometown as he studied ranching practices at the hands of the local cowboys, but I didn’t know that he became president of Aspen’s Chamber of Commerce barely a year after moving there. I remembered from my own childhood the expansive cocktail parties my grandparents threw, but I didn’t know that these parties differed from the ones they attended back in suburban Chicago because of their inclusiveness: in Chicago the guest list was restricted to members of their own social circle, but at Aspen parties, ranchers and business owners drank and traded stories side-by-side with ski instructors and landscapers.

Even though my aunt’s memoir was intended to be primarily about her own life, it was her years growing up in my grandparents’ household that caught my imagination most and filled in the gaps in my knowledge of my family.

So once both of my grandparents were gone and I was asked what items in their house I might like to inherit, I requested the Chelsea clock, because every time I look at it, I’m reminded of the very happy feeling of walking into my grandparents’ house.

My grandmother didn’t do much in the way of housework; she had a privileged upbringing which included domestic help for her entire life. (“Even as a newlywed, which appalled my dad,” my aunt told me during our interview about her parents’ early life.) But one task she did take ownership of was winding that clock, every Sunday. Perhaps because so little was expected of her in terms of domestic duties, she seemed inordinately devoted to that weekly ritual.

And I did the same once I inherited the clock: kept the key with its straight teeth and lacy wrought-metal grip next to the clock on a shelf and wound it every Sunday. Until one day the key disappeared.

I searched for weeks, as the clock ran itself all the way down and eventually stopped. But the key was gone.

I was distraught about this turn of events. My grandmother, perhaps due to her lifelong dependence on a cadre of housekeepers, nannies, groundskeepers, gardeners, cooks and chauffeurs, was rather notorious within the family for the ease with which she lost material possessions. She treated expensive things casually, to say the least. She dropped things, forgot things, left things behind – jewels; credit cards; purses – with little apparent concern for ever seeing them again. She once lost her emerald engagement ring during lunch by the swimming pool; as far as we know, below the wooden slats of the pool deck that emerald sits to this day.

I, on the other hand, had a nearly unbroken streak of never losing anything. At the age of forty, I’d never misplaced car keys or a wallet, never left a credit card at a restaurant, never forgotten the whereabouts of a wristwatch.

So losing the Chelsea clock key wasn’t just disappointing; it was an affront to my previously impeccable record. And not only that, but I’d lost something that my famously careless grandmother had managed to hold on to for seventy years.

Despite the fact that I saw my misdeed as a moral failing of sorts, it wasn’t hard to find a solution. From church, I was acquainted with a traditional clockmaker who I suspected could help me find a replacement key.

Armed with a close-up photo of my clock, I went to visit Richard in his basement workshop. Hundreds of clocks of every possible style and vintage ticked all around us as he examined the photo. Finally he said, “Are you absolutely sure the key is gone? Because Chelsea clocks with their original keys are quite valuable these days. Your clock is really worth a lot more with its original key than with a replacement.”

“Richard, you’re breaking my heart,” I confessed. It wasn’t that I cared about the monetary value of the clock; it was just that his pronouncement was compounding my shame at losing it. “I’ve looked everywhere. Things don’t usually just disappear on me. But it’s really gone.”

Richard took down a catalog that looked like something from a Dickens novel: what appeared to be thousands of filament-thin pages, each one covered with black-and-white illustrations of clocks and explanatory text in the tiniest font I’d ever seen. Without so much as checking an index, he flipped the catalog open to a page of keys. And right in the middle of the page was an image of an ornate old-fashioned key with teeth like tiny straight lines and a lacy wrought-metal grip, identical to mine.

“That’s it!” I exclaimed as if it was a photo of a friend I hadn’t seen since childhood. “That’s my key, exactly!”

Richard looked up, puzzled. “That’s the one you lost?” he asked. “That’s not an original Chelsea clock key. That’s just an inexpensive replacement version. The original looks like this.” He reached for a different book, this one not a parts catalog but more of an archival volume of clocks past, with glossy full-color photos. He opened this book to an image of a very different kind of key: solid burnished bronze with a signature etched into the side.

“No,” I said, confused. “That doesn’t look like mine at all. The other one is what I had.”

Richard smiled. “Well then, no need to feel so bad. You were using a replacement key all along. Someone else must have lost the original before the clock was yours.”

Someone else had indeed. My grandmother. My feelings of shame and ineptitude dissipated. Yes, I’d broken my streak of never losing anything, and yes, I’d apparently been careless. But I no longer had to feel quite so inferior to my grandmother on this score. My grandmother, loser of valuables of all kinds, had lost that key long before I had lost its replacement.

Richard ordered me a new key. It cost about fifteen dollars, and he refused reimbursement, asking me to put the money in the collection plate at church instead.

The fate of the key didn’t stay a mystery for long. Although unlike my grandparents, my husband and I don’t have a full staff of domestic help, we do have a housecleaner who comes in for a few hours once a month. I asked her to keep an eye out for the clock key. She looked surprised. “But you always keep it on the shelf right next to the clock,” she said. I could only concur. “I bet I know what happened,” she said thoughtfully. “I bet you were dusting the shelf and stuck the key in an apron pocket just to get it out of the way while you dusted and it became wadded up with some paper towels or Kleenexes and then you accidently threw the whole bundle away.”

As she narrated this vision, I looked at her, in her housecleaning apron with the big pocket in front that bulged with a wad of paper towels, dustcloth in hand. I knew she wasn’t trying to be duplicitous and didn’t realize that she was actually issuing a confession, but I realized that’s probably just what happened – except it wasn’t me doing the dusting, it was her.

I might have liked to think that my grandmother decided to prank me by swooping down from the spirit world to steal the $15 clock key, but it wasn’t a ghostly visit; it was just our housecleaner being absent-minded.

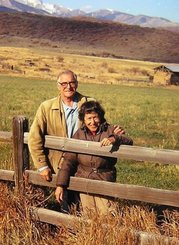

But not long after, I did get a visit from my grandmother’s spirit, at least that’s what I believe happened. Working on my aunt’s memoir had made me think more often about my grandparents, and we’d started collecting photos for the book as well, including a favorite one of my grandparents leaning against a fence on their Aspen ranch. On May 3rd, my grandmother’s birth date, I woke up thinking about her. Later that morning I sat down at the kitchen table to post the photo and a remembrance of her on Facebook, knowing it would bring back happy memories for my mother and her sisters, and for my sisters and my cousins.

As I finished typing the Facebook post, I noticed something peculiar. On the kitchen table, a few inches to the left of my laptop, something was sparkling. Something very small and white and pointy. A sequin from one of my daughter’s hair clips? An ice chip from a box of frozen vegetables?

I picked it up. It was the diamond from my engagement ring. Despite having stayed nestled in its prongs on my finger for the past twenty-six years, it had at some point while I was writing the Facebook post honoring my grandmother’s birthday popped loose and fallen silently onto the table.

I couldn’t help but feel delighted with the obvious gesture from my long-gone grandmother on the 107th anniversary of her birth. Because indeed, what better way for my grandmother to make her voice heard on that morning than through the near-loss of valuable jewelry?

I thought of everywhere I’d been in just the first few waking hours of that day. Throughout my house. In the car. On the driveway. At the supermarket. Running on a gravel footpath in the center of town. Yet the stone in my ring just happened to pop out on a tabletop, perfectly within my range of vision. Had I not been generally complimentary of my grandmother in the birthday post, perhaps she would have chosen to do otherwise.

I put the diamond and the ring, with its now-empty setting, into a plastic baggie to take to the jeweler and silently thanked my grandmother. For having had such an interesting life and a quirky, memorable personality. For putting down roots in Colorado, where my husband and children and I continue to vacation every year. For paying me a visit on that particular morning and making her voice heard in her own unique way. I was so fortunate to know her for nearly forty years. And now I’m fortunate that my work as a personal historian is helping me to understand even more about her life.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed